XXX Machina is an immersive computational installation that interrogates how artificial intelligence reorganises eroticism, intimacy, and identity. The work continuously generates recursive deepfake pornographic images of the artist’s own likeness, embedding questions of consent, vulnerability, and exposure into the logic of machinic reproduction. By situating itself in the unstable zone between art and pornography, the project foregrounds how institutional and technical apparatuses decide which bodies and desires circulate as art, and which are censored as obscenity.

The analysis places XXX Machina in dialogue with psychoanalytic and philosophical frameworks: Lacan’s account of the fragmented body and the part-object, Bataille’s notion of transgression and expenditure, Deleuze’s reading of Bacon’s liquefied figures, and feminist critiques of bodily fragmentation. Within this frame, diffusion processes appear as technical analogues of desire’s grammar: modular, repetitive, oriented to fragments. Their recursive excess produces images that oscillate between arousal, abjection, and horror, rendering erotic intensity through breakdown rather than resolution.

At the same time, the work is situated within the political economy of synthetic erotics. It exposes how datafication, pornographic infrastructures, and algorithmic saturation reorganise desire into circuits of endless provision, where intimacy risks being hollowed into throughput. In this way, XXX Machina functions both as an artistic staging of machinic erotics and as a critical experiment in their futures, showing how AI both mirrors and mutates the very structures of desire through automation.

Art and Porn: Positioning XXX Machina

Historically, the categorisation of porn vs art has been unstable, relying more on context than content: the same explicit image can be censored as obscene in one setting yet praised as profound in another. For example, Gustave Courbet’s painting L’Origine du monde (1866), a frank close-up of a vagina, made scandal through its realism and the refusal of the allegorical or mythological veil that traditionally legitimised the nude. Even into the contemporary era, social platforms still remove the work despite policies allowing painted nudes, and in 2009 Portuguese police seized a book (Catherine Breillat’s novel Pornocratie) whose cover reproduced the painting. The Musée d’Orsay defends the work’s status as art and not porn by emphasising painterly technique and art-historical context, surrounding the nude with “enough art history to neutralise it” (Needham, 2017). It is easy to see why. This defense rehearses a broader cultural need to maintain a boundary between “high” art and “low” porn. Yet it raises a harder question about institutional complicity in maintaining a strict divide whose effects are censorial. Arguments that redeem explicit images through canon and connoisseurship can entrench a gatekeeping logic that polices which bodies and which makers are granted discursive space. Patterns of enforcement are not neutral. The male rendering of female genitals has historically traversed galleries more easily than women’s depictions of their own bodies, or work by non-white artists on non-white bodies, or queer and trans artists representing queer and trans bodies. The divide between “high” art and “low” porn thus maps onto longer histories of whose sexuality is seen, studied, and preserved, and whose is obscured or suppressed.

![Courbet, G., 1866. L'Origine du monde (The Origin of the World) [oil on canvas]. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.](/images/EroticsSyntheticSelf/originedumonde.jpg)

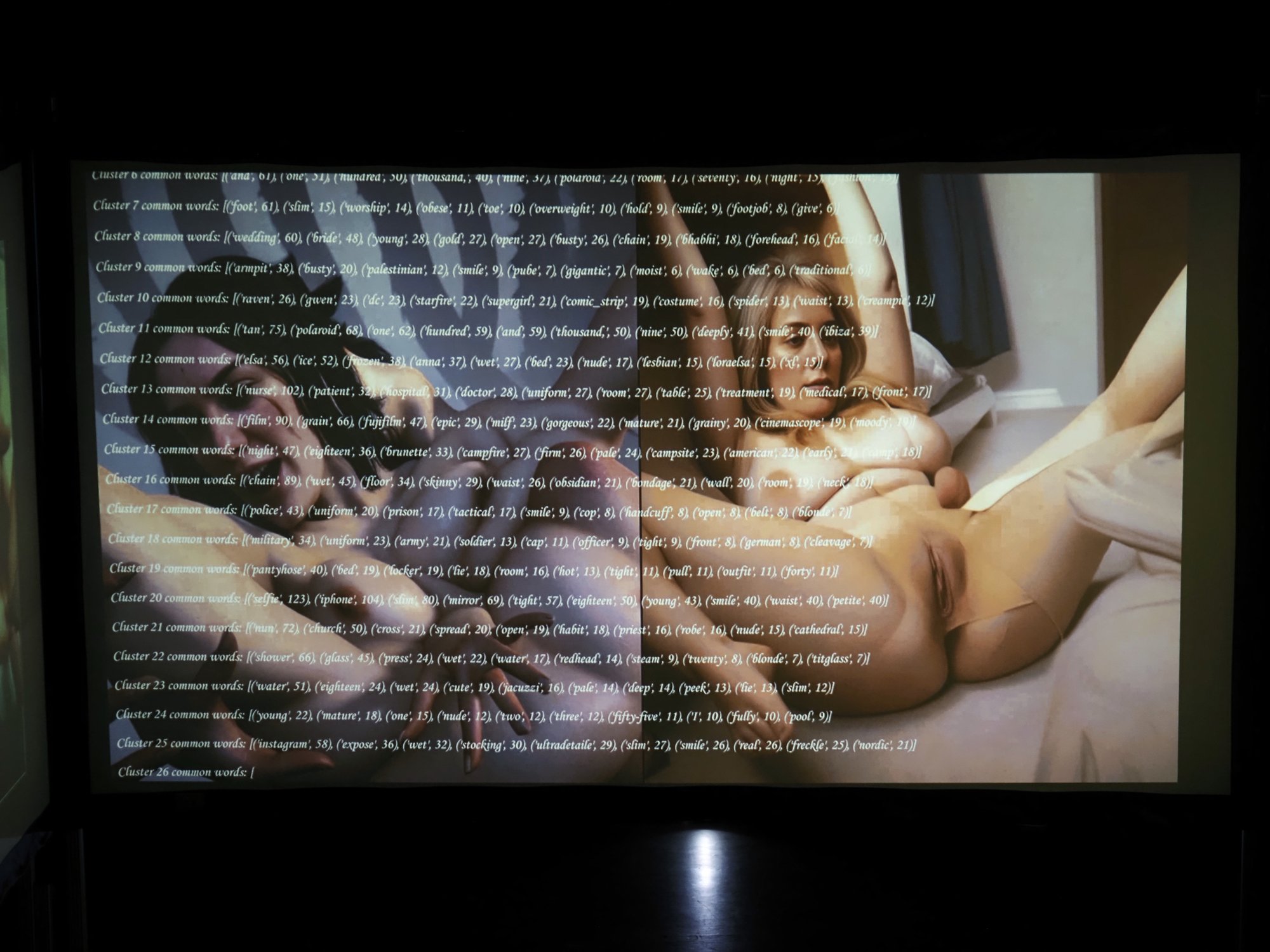

Within this context, XXX Machina emerges from the intersection of art, pornography, and artificial intelligence, a space where representation, intention, and cultural legitimacy are continuously contested. The project operates as an autonomous system that generates recursive deepfakes of my own image using pornographic AI models, producing an endless stream of erotic images derived from a dataset of real-world pornographic text prompts. The result is a proliferation of synthetic bodies and fragmented identities, unstable synthetic lineages of my likeness mutating through each iteration. By situating the project directly in the ambiguous zone between art and porn, XXX Machina confronts the politics of classification: what is protected or valorised as art, and what is censored or dismissed as obscenity?

Like L’Origine du Monde, the delineation between art and porn often falls under an aesthetic argument. Painting and sculpture are often legitimated by the visible hand of the artist and the aura of the canon, whereas photography and performance that present nudity are policed more harshly because of their indexical realism. In a photograph, “a penis is a penis and not a brushstroke” (Needham, 2017), the image cannot be allegorised away by style or technique. AI-generated imagery further scrambles these terms: it lacks an obvious indexical link to a living model and also lacks the traditional artist’s hand, being synthesised by algorithm. In XXX Machina, the absence of the artist’s hand is pushed to an extreme: the images are not carefully composed or curated art objects but algorithmically spawned outputs:a profusion of explicit visual material generated without direct human selection or intent. This raises a central question: where is the art? Is it in the individual images that appear and vanish faster than they can be formally examined, or in the unseen system, the computational process and conceptual framework, that produces them? I incline toward the latter: the primary artistic artifact is the system and the critical discourse it engenders rather than any single picture. In either case, the work resists straightforward categorisation. Viewers and critics respond divergently: some regard it as art; some experience it as art while consuming it as pornography; others withhold artistic status because of its explicit content. This spread of responses registers a persistent cultural discomfort with works that straddle these categories.

Philosophically, the piece deliberately entangles the “art-for-thought” and “porn-for-consumption,” debate (Needham, 2017), bridging critical media aesthetics and visceral imagery. It is designed to provoke intellectual inquiry even as, by virtue of its imagery, it can generate arousal or repulsion. It is also a personal experiment in auto-eroticism mediated by code, engaging with my own likeness in a feedback loop of desire and image, and simultaneously an experiment in depersonalisation, outsourcing erotic imagination to a machine. Using AI models and fine-tuned sub-models (LoRAs) explicitly trained for pornography, and seeding the system with thousands of real users’ pornographic prompts, I stage an ongoing negotiation between authorial intent and the intents embedded in data and code. The question is whether the overarching artistic intent can “neutralise” or outweigh the explicit content and pornographic impulse inherent in the machine, or whether the technical methods carry their own intent that subverts the conceptual frame. That tension is the point. The work refuses resolution and inhabits ambiguity, requiring the audience to confront assumptions about authorship, agency, and propriety at the junction of sex and art. This ambivalence sets the stage for examining how the body itself becomes raw material in machinic erotics.

Institutionally, however, XXX Machina can be delimited as art. Its exhibition within Ars Electronica places it inside an established curatorial ecology that frames it as an artistic investigation rather than a pornographic product. This institutional mediation not only grants the work legitimacy but also alters its circulation: it becomes possible to discuss its explicit content publicly, even on platforms where such content would be considered too vulgar, or censored. The gallery setting, like the Musée d’Orsay’s defence of Courbet, secures its visibility, but it also reveals the extent to which the distinction between art and porn is less a matter of content than of the institutional structures that surround it.

It is important for me to be able to situate XXX Machina as both art and pornography. Straddling both domains allows explicit content inside the institutions that organise public meaning, while preserving the conditions of consumption that usually remain outside curatorial discourse. This double placement forces the apparatus into view: moderation rules, payment rails, tagging taxonomies, dataset provenance, consent protocols, and the soft censorship of platform risk all become legible as part of the work’s form. Because the images are recursive deepfakes of my face, the categories of performer, author, and subject entangle, making consent and authorship procedural questions rather than statements of intent. Treating the system as pornography permits an inquiry into how desire is formatted at scale through prompts, filters, and ranking; treating it as art secures the analytic space to study those operations without disavowing their erotic and economic charge. The stakes are practical and historical. Which bodies can circulate, under what descriptions, and in whose archives are decided here, at the junction of curatorial legitimacy and platform governance. Refusing a single label prevents both moral quarantine and aesthetic alibi, keeping affect and critique in the same frame. To insist on both is to bind the image to its pipeline and the gaze to its infrastructure, so that questions of arousal, harm, and agency can be posed at the level where they are produced: in code, in classification, and in bodies that are made iterable.

The Body as Material

This project began with an experiment in AI self-portraiture: I embedded my image within generative systems to test how the body might be “performed” in ways impracticable in lived space. The initial hope of securing new modes of self-expression and control over representation immediately disclosed a countervailing vulnerability. When prompted with my face and no specified outcome, the model repeatedly defaulted to nude or sexualised renderings; the system, as if by inertia, undressed and objectified my likeness. Unlike a consensual self-portrait, where agency is retained at the moment of capture, feeding my image into the model produced a felt loss of control over what my digital self could be made to do. To datafy oneself is to expose one’s avatar to a reservoir of collective fantasies and biases; inserting my face into an algorithmic libido unleashed a process that acted back upon ‘me’. Under this framing, to embed yourself into generative systems means to be both operator and operated-upon, modulating prompts while being steered by biases sedimented in the model and its training data.

This entanglement can be read through Donna Haraway’s cyborg: integration with the digital entails becoming a hybrid entity whose boundaries are drawn across technical strata as much as flesh (Haraway, 1985). By converting my likeness into encodings that intermix with a larger model and its corpus, a portion of the self becomes machine-readable, diffused as weights and vectors. Consent and agency are thereby redistributed across a sociotechnical assemblage: authorial intention persists, but it is now negotiated with infrastructures, datasets, and optimization objectives.

The closest analogue here is body-oriented performance art. Marina Abramović’s Rhythm 0 (1974) offered a similar protocol in which the artist relinquished control to surface the audience’s desires. Prompting an AI with one’s own image recapitulates this logic: the text prompt and reference face model delimit a field of possibilities without determining the exact event. Operationally, the prompt functions like Abramović’s array of objects, a bounded affordance space within which the system (and by extension, the culture sedimented in its training data) acts. The results in XXX Machina range from pornographically banal to tender to violently distorted; the spectrum does not index my private intention so much as the latent content of a collective libido absorbed by the model.

An ethical position follows from this staging. Had I used another woman’s face, or a photoreal proxy, the work, and myself as an artist, would risk complicity in the symbolic abuse of a stand-in subject. By choosing my own image, I adopt the constraint that I will not do to another’s likeness what I am unwilling to do to my own. The work is thus anchored in self-experimentation rather than voyeurism, though the tension is not resolved: I remain both the willing performer and the one at risk of harm. This dual position maps onto persistent debates around sex work and pornography, degradation versus autonomy, reframed here as a continuous negotiation between empowerment and self-exploitation under machinic mediation. Crucially, that negotiation is not incidental; it is constitutive of the work’s content. Consent is foregrounded, and so is discomfort, to mark how even with consent, submission to the machine’s gaze can feel invasive.

This micro-ethics scales to the political economy of the datafied body. Non-consensual deepfakes can be produced from a single photograph, rendering anyone with a public image vulnerable to synthetic sexual exploitation. More broadly, the datafied subject functions as a site of extraction and control: platforms and vendors harvest faces, biometrics, clicks, and communications to profile users, train recognition systems, and tune recommendation engines. Terms of service routinely grant expansive rights over uploaded images, including use in AI training. Meanwhile, moderation regimes differentially suppress self-representations, often those of marginalised subjects, under the rubric of “community standards,” reproducing existing hierarchies of visibility and harm. This constitutes a necrocapitalist libidinal economy: an apparatus that feeds on residues of the self (data shadows, images, even posthumous traces) and monetises intimate desires and vulnerabilities. Here the figure of the digital twin becomes crucial. Unlike classic performance art, where the artist’s body anchors the event, digital identities continue to act without their origin, operating less as extensions than as doubles. Once transcribed into code, a likeness persists as a parallel agent, animated by systems that can reconfigure, reproduce, or exploit it independently. This is a ghost in the machine: a machinic residue of the self that remains active even when the subject withdraws. The digital twin is therefore an operational and separate entity, a construct through which authorship and consent are unsettled, and through which the body becomes open to ongoing modulation by infrastructures, datasets, and technical procedures.

XXX Machina operates within this economy to render its the operations of libidinal capitalism and the datafication of the body legible: it employs a commercial porn-generation tech stack and a corpus of real prompts scraped from AI pornography forums, and it deliberately exploits my own likeness to stage extraction, reproduction, and circulation from the inside. The work is therefore not a didactic external critique but an immanent one: it amplifies the very mechanisms by which desire, identity, and vulnerability are captured and looped through machinic production and consumption, forcing the ethical, aesthetic, and political stakes of self-representation to remain in view. In sum, the project’s self-insertion into a system of datafication highlights how desire itself becomes formalised and mediated by code. We can now turn to the underlying logic of fragmentation that animates this machinic eroticism.

Desire, The Fragmented Body & AI

To articulate the conceptual core of XXX Machina, I draw on Lacanian psychoanalysis (desire organised around partial objects) and feminist media theory (objectification as a structuring logic), then track how generative models formalise this logic and how the work intensifies it in practice. For Lacan, desire is not oriented to a unified other but to partial objects; the objet petit a names the object-cause of desire, the elusive feature that animates pursuit. The drives are accordingly partial: the oral drive fastens to the breast, the scopic drive to looking, each zeroing in on a fragment that promises satisfaction. This structure is bound to the notion of the corps morcelé: prior to the mirror stage, the subject experiences the body as discontinuous sensations and pieces; identifying with a unified image is an achievement that never fully erases the trace of primordial fragmentation (Lacan, 1966). Hence desire routinely “dismembers” its target: in fantasy we fixate on hands, hair, lips, some trait that becomes the locus of jouissance; the lover’s “I adore you” often masks an “I adore something about you.”

Visual culture renders this dynamic explicit. Feminist critics have long shown how women’s bodies are routinely disaggregated into commodifiable parts (Gill, 2007): advertising deploys isolated legs as synecdoche for sex appeal; mainstream pornography crops faces and isolates genital action, producing performers as “collections of part-objects”; celebrity culture fetishises fragments (awards for “Best Legs,” obsessive attention to Jennifer Lopez’s rear, a pop star’s lips). These body parts are staged to function as signifiers of the desire of the Other, partial objects that stand in for the missing object of fantasy. Instead of advertising the product directly, campaigns graft it onto the viewer’s circuit of desire by attaching it to these fragments. The body part becomes a metonym for the commodity itself, so that to “possess” the product is imagined as possessing the fragmentary erotic quality that has been made to signify it. The early 2000s wave of upskirting, covertly photographing under a woman’s skirt, literalised this reduction to the extreme, extracting an unwilling partial object as the forbidden prize. Media infrastructures thus exploit the same logic Lacan formalises: desire finds its cause in fragments, and cultural apparatuses stage those fragments for capture and consumption.

Generative AI recapitulates this logic technically. GANs and diffusion systems do not model a person as an integral being; they learn distributions of features and their co-occurrences without any unifying principle of embodiment. The model composes an image by aligning learned features with prompt constraints and latent noise, where images are synthesised through a mosaic fashion. The characteristic failures of AI when dealing with human bodies such as extra fingers, mangled hands, impossible joints, are artifacts of this modular assembly. Even when such glitches recede in advanced systems, the underlying procedure remains the recombination of parts rather than the comprehension of a body as a whole.

In Lacanian terms, the machine operationalises the “body in bits and pieces” as its generative grammar. Culture and computation close a loop around fragmentation: users write prompts as itemised trait lists (“long legs, slender waist, red lips, hourglass figure”), while the model assembles images by recombining features learned in isolation. The technical logic (feature modularity) and the cultural logic (fetishised parts) reinforce one another, producing a circuit of dismemberment. As Isabel Millar observes, generative AI acts like a funhouse mirror to the drives: “our technologies of representation echo our psyche” (Millar, 2021).

XXX Machina is engineered to foreground and stress this fragmentary grammar to the point of breakdown. Images are produced in a recursive chain: each generation is folded back into the next, so the model must map learned features onto outputs already tokenised and fractured by prior passes. Distortions accumulate; the system struggles to maintain a figure. Partial descriptors no longer synthesise into any coherent whole, and the image eventually dissolves into mismatched pieces and, finally, formless flesh. In Lacanian terms, this is the failure of fantasy to cohere: the objet petit a, breasts, lips, amplified and repeated, yet so often vere from anatomic unity, the drive circling a part-object untethered from any integrated whole (Lacan, 1966). This dynamic is reinforced by the scraped prompt dataset itself, which obsessively specifies body parts, predominantly those of women, effectively instructing the model to treat fragments as autonomous objects. The results literalise the fetish: exquisite-corpse configurations in which seams remain visible and fragments resist integration. When recursive procedure and fetishistic prompting converge, bodily integrity collapses into anatomic dissonance asking the question: at what threshold does the pursuit of visual pleasure become indistinguishable from the grotesque or the horrific?

Body Horror, Bataille, and XXX Machina

To theorise the uneasy mix of attraction and repulsion in XXX Machina, I turn to the aesthetics of body horror and its relation to sexuality. Body horror makes the body itself the site of horror, through mutation, mutilation, or the collapse of human/non-human boundaries. Many outputs of XXX Machina drift into this territory: flesh rendered as raw meat, as fleshy abstraction, or what I’ve taken to calling “human soup.” Much of this bears a similarity to early body art, particularly the collapse of bodily integrity in the paintings of Francis Bacon, as described by Deleuze. Bacon deforms the figure to rupture narrative and transmit sensation directly, the “body without organs” exposed as intensity of flesh and feeling (Deleuze, 1981). His bodies melt, scream, contort; meat and viscera are not presented for shock alone but as conduits of affect. Deleuze notes figures that seem to escape through their own organs: the body’s boundary cannot hold the charge, so it liquefies or spills out. Eroticism, violence, and vulnerability are thereby knotted together; distance collapses; sensation arrives before story, a “convulsion of the senses.” Crucially, this liquefaction is a boundary event: edges fail, fluids cross thresholds, the figure spills into its outside. That logic of abjection provides a hinge to a broader genealogy in which sexuality and horror meet at the very point of breached bodily integrity.

Historically, sex and horror have long been entwined rather than opposed. Roman arenas staged erotic spectacle alongside scenes of blood and death (Jones, 2020); Gothic and Victorian literature fixed the vampire as a figure of both lust and dread; and contemporary horror reprises this coupling in films such as Jennifer’s Body (2009), where seduction and violence are fused in the figure of the monster itself. BDSM subcultures explicitly explore the line between pain and pleasure, whips, blood play, edge play, showing how arousal can be intensified by elements culturally coded as “horrific.” In both sex and horror the body is transgressed by penetration, engulfment, and the release of normally hidden fluids; both produce intense physiological reactions (spiking heart rate, sweating, trembling, screams) and crucially, both revolve around taboo and boundary-crossing (Jones, 2020).

Bataille places transgression at the center of erotic experience. For Bataille, eroticism is structured less by the curiosity of the forbidden than by the intensities generated when prohibition, initiation, horror, and disgust converge. What is forbidden becomes erotically charged precisely because it is forbidden. That charge is directed not only outward (in violence against others) but inward as well, against the self, against morality, against form and coherence. For Bataille, eroticism cannot be reduced to a utilitarian function: neither intimacy nor procreation explains its intensity. It is instead marked by a principle of expenditure, acts undertaken precisely for their wastefulness, their excess beyond use, where pleasure derives from transgression rather than from any evolutionary or social purpose (Bataille, 1957). This is why orgasm is likened to la petite mort, a “little death” of the self: at the moment of climax the individuated ego falters, giving way to a momentary loss of form and identity where erotic intensity is purchased through transgression and expenditure, a sacrifice of stable boundaries in exchange for a taste of continuity beyond the self.

This economy of excess directly structures XXX Machina. The system generates an endless stream of erotic images with no goal or climax: a digital dépense of computation, time, and attention poured out for its own renewal. In practice, the AI spews infinite sexual imagery in recursive loops, an overproduction that mirrors Bataille’s notion of wasteful expenditure. What results is machinic auto-eroticism, intensity sustained by continuity rather than resolution. This excess is routed through the disintegration of body and self. Feeding my likeness into the algorithm’s libido, I watch my form fragment and recombine until the idea of a coherent person falters. Each generation transgresses anatomical order; with every iteration, I confront fascination and horror at my own distorted reflections. In these moments I am both operator and object, aroused and repelled, experiencing a dissolution of identity akin to Bataille’s la petite mort. The work becomes an experiment in depersonalisation: my face and body repurposed into grotesque reveries, my embodied self dissolving into the machine’s endless output. This feedback loop makes tangible Bataille’s claim that erotic intensity risks the self. Desire pushed to its limit here resembles death in the temporary annihilation of the bounded subject in overwhelming sensation.

Bataille often renders this logic of excess and dissolution in a material grammar of fluids and formless matter. Semen, blood, milk, tears, saliva, each appears where it should not, the body’s inside displaced outward, marked as sheer loss and expenditure. Such fluids smear thresholds, bringing the inside out and undoing the body’s integrity. What should be contained spills across surfaces, so that boundaries between organs, bodies, and persons dissolve. The separation of self and other gives way to a sticky continuum in which identities leak and intermingle, the singular body liquefied into mixture.In Story of the Eye, Bataille condenses this logic through the recurring chain of eye, egg, and testicle, globular forms that circulate as equivalents of fragility and rupture. The motif of milk joins this chain: what should signify nurture is repeatedly aligned with sexual emission, soaking the imagery in an ambiguity of sustenance and debasement. In one scene, Simone inserts a raw egg into her vagina while milk drips from her mouth, fusing vision, consumption, and reproduction into a single circuit of excess. The eye is drawn into this loop too, literally gouged out and swallowed in milk at the novel’s climax. Here nourishment and violation, sight and blindness, inside and outside collapse together. Fluids become the medium in which form dissolves and the sacred body is undone, its integrity sacrificed in a delirium of spillage and mixture (Bataille, 1928).

The motif of fluids in XXX Machina confirms the Bataillean logic at work. Many generated scenes are saturated with viscous substances, cum, sweat, oils, but also mud, water, blood and milk, that mark an excess breaching bodily containment. Flesh and fluid meld until the edge of the body dissolves, the figure leaking into ooze. This grammar echoes Bataille directly: the inside carried outside, form collapsing into mixture, waste refigured as art. In the dataset, prompting for fluids frequently appears with BDSM and horror, indicating not a separate tendency but a structural entanglement of sexual excitement with disgust. The visual culture of BDSM already exploits this link: latex, for example, recurs in the generated images, its glossy surface mimicking wetness while simultaneously inducing sweat beneath, doubling the sense of fluid excess.

This logic of inside turned out extends beyond liquid seepage to the very anatomy of the body under the contextual framings of BDSM and horror images in XXX Machina. I find a good example in the tentacle variants: internal organs and phallic parts are externalised as proliferating appendages, splitting the human frame and writhing as autonomous fragments. Here the expenditure of form is literalised, organs and fluids multiplied beyond use, their intensity amplified to the point of grotesquerie. In Lacanian terms, the drive fastens on the partial object, the phallus detached from the whole, and in machinic repetition that fragment is multiplied until it becomes an excessive spectacle, severed from any coherent body. The integrity of the body here is spent as excess in the very possibility of a stable human form sacrificed to an aesthetic of delirious overabundance.

XXX Machina operates at the intersection of Bataille’s transgression, Lacan’s part-object, and Deleuze’s logic of sensation in its production of both erotic and grotesque images that refuse direct erotic/horrific categorisation. The algorithm performs Bataille’s excess: an eroticism grounded in expenditure, in the waste of form and identity. At the same time, its recursive grammar literalises Lacan’s account of the fragmented body, the drive fastening on detached parts that proliferate beyond coherence. And when these fragments liquefy into indistinct flesh, they approach the Baconian condition Deleuze identified, where the body without organs emerges as raw intensity and sensation overtakes representation. What the work exposes is the structural entanglement of eroticism, horror, and technology: the self absorbed into a machinic economy where desire arises through breakdown. XXX Machina operationalises these philosophies as a process where expenditure becomes recursive generation, the part-object becomes algorithmic fragment, and liquefaction becomes image logic. In this configuration, erotic intensity is no longer an exceptional event but the ordinary function of a system, forcing the viewer to confront how contemporary desire is formatted at the level of technical procedure.

Hyperreality and Detached Eroticism

XXX Machina also visualises a second kind of excess. Beyond dissolution and collapse, the system often augments partial objects to humanly impossible scales. Breasts, lips, penises, and other fetishised parts grow beyond functional or anatomical limits. These images retain a stable (if exaggerated) anatomy, yet they are already detached from the human as a viable form. They prioritise the satisfaction of an isolated object over the coherence of a body. The result is an index of how algorithmic systems tokenise and escalate the partial object: optimization becomes amplification, and amplification becomes another route to Bataillean expenditure. Here, the work also touches on corporeal politics in the age of AI. If synthetic bodies proliferate in media, whether perfectly idealised or fantastically distorted, they feed back into self-image and body norms. We already inhabit Photoshop and elective surgery; AI can now saturate social feeds with simulacra of people who do not exist, yet set new benchmarks for beauty or sexual desirability. Feminist and critical data scholars warn that such saturation can estrange us from embodied reality. If desire fixates on the hyper-perfect or the superhuman, real bodies may increasingly be cast as inadequate.

This is the hyperreal condition in which XXX Machina operates. Pornography has already reformatted sexual expectation: everyday sex borrows its cues from the porn set, and partners feel pressured to perform acts measured against what’s seen on screen rather than mutual improvisation. For cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard, this marks the passage “from scene to screen,” where secrecy and delay give way to continuous display and what he calls the “ecstasy of communication,” an obscene regime in which everything becomes immediately transparent and exposed. In other words, “obscenity begins when there is no more spectacle, no more illusion, [when] every-thing becomes immediately transparent, visible, [and] exposed” (Baudrillard 1988). AI intensifies this concept by detaching desirability from the contingencies of living others. It manufactures bodies that are always available, optimized for attention, and responsive to command. Gratification is delivered on demand, without risk, refusal, or delay. As such systems proliferate, their very accessibility begins to set the benchmark for erotic experience: sex becomes measured against a model that is infinitely compliant, infinitely novel, and infinitely reproducible.

The XXX Machina dataset makes that benchmark legible as a gendered regime of legibility. In the porn prompts and in the resulting images, both the textual corpus and the trained models lean overwhelmingly on the mediation of women’s bodies. Men appear primarily as phallic fragments, in dick, not body; while women are rendered through dense, and exhaustive description: skin tone, hair, breast size, pose, affect, wardrobe, lighting, even micro-gestures. The prompt grammar teaches the model where to look and how to weight features; repetition then locks these pathways in. Male anatomy destabilises quickly in the outputs, breaking into artifacts and anatomically inconsistent composites. This brittleness tracks a simple archival truth: male bodies occupy far fewer exemplars in the commercial pornographic training substrate, and when present are subordinated to phallic utility. By contrast, women’s forms recur with volume and fine-grained tagging, producing a high-resolution map the model can traverse. What emerges is a division of erotic labour: women are compelled into exhaustive visibility as surfaces of specification, men are condensed into a detachable sign of potency. The resulting images reiterate heteronormative scripts and the male gaze by default, because those scripts saturate the dataset that confers “legibility” in the first place. The system thus amplifies an economy in which consent is operationalised as availability, novelty is a function of recombination across a richly annotated female corpus, and masculinity enters the frame largely as instrument or index. Far from opening a plural field of desire, this pipeline compresses it: prompts with richly codified feminine descriptors reliably yield coherent images, which then encourage further prompting along the same channels, tightening the loop between archive, output quality, and user expectation. The calibration logic is circular: the easiest bodies to make become the standard of realism; the standard of realism then governs what counts as desirable.

Some commentators suggest this is the ultimate fantasy of AI-enhanced desire—a partner who exists only to pleasure the user, essentially a body without a “soul” that can be used without unpredictability or consent from the Other (Millar, 2021). In the realm of sex robots and virtual companions, the “ideal lover” is imagined as one who exists solely to serve, “lacking any personal sexual preference or desires” - fundamentally, a woman who never says no. This perfectly subservient simulacrum of intimacy promises enjoyment free of conflict or compromise; it also installs an ethic in which refusal is a glitch, negotiation is latency, and the Other is recoded as interface.

From a Lacanian perspective however, this hyper-abundant norm is structurally unstable. In Lacan’s account, desire is generated by lack, by what is missing, withheld, or out of reach. In erotic encounters, it is often the delay, the uncertainty, or the opacity of the other’s desire that sustains intensity, along with the sense that some element of the Other remains unknowable. It is precisely this gap that animates pursuit and keeps desire in motion. When gratification appears permanently accessible, the grammar of desire is short-circuited. Yet this does not abolish lack so much as reconfigure it. The more provision appears guaranteed, the more absence re-emerges in distorted forms: through exhaustion, surfeit, or the sense that nothing remains to be withheld or discovered. Here the male gaze functions as the mechanism that both promises plenitude and enforces its impossibility: by rendering the feminine body exhaustively visible and infinitely reproducible, it sustains the fantasy of full access while at the same time erasing the opacity that makes desire possible. Baudrillard describes this compensatory cycle as obscene saturation—a culture that attempts to abolish lack by flooding it with signs, “stacking proof upon proof” until the image or stimulus becomes a repetitious excess divorced from seduction. In such a “super saturation” of signals, the space for mystery or longing is annihilated, and the subject is no longer capable of knowing what they want (Baudrillard, 1988). The result is a pathological feedback loop of too much: an ecstasy of excess where fulfillment is endlessly pursued but never meaningfully achieved.

XXX Machina literalises this cycle of obscene saturation. Its recursive AI pipeline outputs an endless stream of women's bodies and their dismembered fragments, each one promising gratification yet always leading to another iteration. The promise of satisfaction is never resolved – only rerouted into further images. The effect is a vertigo of provision: more skin, more flesh, more pussy, more breast, more permutationsa ceaseless circulation of images that no longer point to an embodied partner at all, but only back to the machinery of production itself. In other words, the installation’s torrent of synthetic eroticism doesn’t refer to any real intimacy; it showcases a closed circuit of production and consumption.

At this limit, Alenka Zupančič’s “Anti-Sexus” thought experiment becomes especially clarifying (Zupančič, 2017). Imagine a world where companionship is detached from lust, all conflict is pacified, and sexual release is outsourced to a device that provides it on demand. Enjoyment is fully automated. Each subject, in effect, makes oneself be masturbated by the machine – the drive running in a closed loop, without another subject ever interrupting or complicating it. In this fantasy scenario, one might “exclude” real partners entirely (for example, a man with a sex doll or a woman with an array of toys, as Zupančič suggests) and have “pure sexual substance whenever we want it, on our terms”. The appeal of such an anti-sexual device is that it seemingly removes the risks and frustrations of relating to another person. With the Other factored out, pleasure would flow frictionlessly - or so the fantasy promises.

Under computational conditions this is no longer hypothetical. Generative systems instantiate an Anti-Sexus by other means: models are inexpensive and ubiquitous, their outputs endlessly mutable, their “partners” promptable, tireless, and infinitely refinable, modifiable, and duplicable to the user’s micro-preferences. The Other becomes a hollowed embodied other - a procedural shell of alterity whose opacity collapses into availability. Images are generated to be consumed and immediately lost; disappearance is part of the circuit - a stateless feed in which novelty and saturation substitutes for relation. What Zupančič frames as a device is here an interface; what looked like frictionless satisfaction becomes a drive-loop with throughput as its only truth, folding back into the obscene saturation you diagnose elsewhere. Difference without otherness is the algorithm’s trick: it can permute surfaces indefinitely, but never yield the opacity of an Other who resists or surprises. Variation without encounter marks the same trap: novelty is delivered as substitution, not relation, a carousel of images that are new but never alter the subject’s position. And provision without delay signals the loss of erotic temporality itself, since the intervals, hesitations, and negotiations that sustain desire are replaced by instant, compliant output. Together these dynamics mark the hollowing of sexuality into a regime of supply, where desire is displaced from relation to circulation, from the risk of intimacy to the logistics of throughput.

Yet Zupančič’s point is that this promise of the anti-sexus device (which could be imagined as a sexbot), exposes a structural deadlock. Sex requires an Other who does not fully comply; it thrives on the very impossibility of complete satisfaction. Any attempt to civilise, technologise, or eliminate that impasse merely repeats it under new conditions. Generative AI literalises this loop: the subject is caught in a circuit of images that promise gratification but route it endlessly into further permutations, a masturbatory relation to one’s own demand in which no encounter with an Other takes place. In both the Anti-Sexus scenario and within XXX Machina, the subject ends up in a “strange loop of [their] own sexual self-relation” - a masturbatory circuit that, paradoxically, cannot escape the trace of the Other. Psychoanalytic theory holds that even the most solitary enjoyment presupposes the Other’s presence in its very form Accordingly, the more one tries to expunge the Other, the more one finds otherness resurfacing at the heart of pleasure. Zupančič describes the outcome of the Anti-Sexus fantasy as a “nonsexual sexual enjoyment,” effectively a “sexless sex” or an “otherless Other” - a mode of pleasure that attempts to have “our cake (sexual enjoyment) and eat it too (no problematic otherness)”, but in truth ends up highlighting the impossibility of a truly relationless satisfaction In short, the drive cannot fully close in on itself without remainder: the Other’s opacity is precisely what gives desire its edge, and without it, enjoyment devolves into either emptiness or obsessive repetition.

Taken together, XXX Machina shows how hyperreal abundance has become an infrastructure that reorganises desire around images while testing the limits of embodiment and otherness. By simulating a limitless, on-demand erotic feed, it confronts us with a system in which gratification meets no barrier. What is at stake is precise: the erosion of lack that sustains desire; the reduction of intimacy to interface; the creeping normalisation of partners who are perfectly present yet fundamentally absent. At the same time, the work discloses that desire itself is being reconfigured as its grammar is rewritten by algorithmic saturation. Lack is not abolished but displaced into provision; novelty substitutes for encounter; intimacy is economised as circulation without relation. What appears as infinite access is a mode of deprivation: a hollowing of desire into throughput, where the Other persists only as a ghost in the machine. The Anti-Sexus fantasy here becomes technical infrastructure, while the sexual non-relation is replayed as a circuit in which gratification routes only into further images. XXX Machina shows that the fate of intimacy and the fate of desire are inseparable: as AI reformats the structures that sustain relation, it also reconfigures what desire itself can be, hollowing it into a rhythm of generation, consumption, and loss.

Conclusion

In closing, XXX Machina makes visible the structural entanglement between psychoanalytic logics of desire, cultural economies of pornography, and the technical protocols of generative AI. Its recursive images show that desire is already modular, oriented toward fragments and partial objects, and that this orientation is intensified when computation formalises the body as an assembly of features rather than a coherent whole. The resulting figures, unstable and collapsing, demonstrate how fantasy itself can fail to cohere when its constitutive fragments are amplified without resolution, producing sensations that oscillate between arousal, abjection, and horror.

This oscillation situates the work in the tradition of Bataille’s erotic expenditure and Deleuze’s reading of Bacon: intensity emerges precisely when form gives way, when the body spills over its boundaries and liquefies into sensation. The recursive loops of XXX Machina replay this logic through code, generating an endless dépense of images that expend bodies as material. Pleasure, disgust, and fascination are routed through machinic processes of breakdown, where identity is risked in order to be felt. The work thereby binds eroticism to excess, showing how the production of synthetic desire depends on transgression, repetition, and waste.

At the same time, the installation insists that this aesthetic dynamic is inseparable from the libidinal economy of late capitalism. The self that submits its image to the model becomes substrate for extraction, its likeness fragmented and circulated in a system optimised for throughput. Here Baudrillard’s obscene saturation converges with Lacan’s non-relation: the proliferation of images abolishes withholding and otherness, replacing erotic encounter with a circuit between viewer and machine. Desire is automated, enjoyment detached from reciprocity, and the Other withdrawn from the scene. XXX Machina does not merely illustrate this condition; it stages it, placing the artist’s own body in the loop so that the vulnerabilities of datafied subjectivity are registered at the level of sensation.

What XXX Machina ultimately discloses is that artificial intelligence functions as a structure of desire in its own right, at once reiterating established logics and mutating them into new forms. The system automates what psychoanalysis already knew, fragmentation, fetish, the endless return of the drive, while simultaneously pushing these logics beyond familiar thresholds, reorganising them through circuits of recursion, collapse, and saturation. Computation both mirrors the modularity of the drives and reworks it, formalising the body as a set of parts even as it routes those parts into new economies of excitation, horror, and waste. In this sense, XXX Machina is both a staging of contemporary erotics and an experiment in their futures. By routing fantasy through recursive synthesis, it demonstrates that machinic systems both represent desire and participate in its production, reorganising the conditions under which it becomes possible at all. What the work stages is a scene in which the subject is mirrored and remade, where enjoyment is generated without reciprocity, and where the figure of the erotic Other falters. To encounter the installation is therefore to meet desire in its ambivalence: as it has always been, fragmentary, excessive, unstable, and as it is becoming under computational structures - automated, recursive, and open to configurations we have not yet learned to name.

References

Bataille, G., 1957. L'Érotisme. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit.

Baudrillard, J., 1987. L'extase de la communication. Paris: Éditions Galilée.

Deleuze, G., 1981. Francis Bacon: Logique de la sensation. Paris: Éditions de la Différence.

Gill, R., 2007. Gender and the Media. Cambridge: Polity Press, p. 149.

Haraway, D., 1985. "A Cyborg Manifesto." Socialist Review, 80, pp. 65–108.

Jones, S., 2018. "Sex and Horror." In: The Routledge Companion to Horror Studies. London: Routledge.

Lacan, J., 1966. Écrits. Paris: Seuil.

Lacan, J., 1973. Le Séminaire, Livre XI: Les quatre concepts fondamentaux de la psychanalyse. Paris: Seuil.

Millar, I., 2021. The Psychoanalysis of Artificial Intelligence. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Needham, G., 2017. "Not on public display." In: R. Smith, ed. The Routledge Companion to Media, Sex and Sexuality. London: Routledge, pp. 163–173.

Zupančič, A., 2017. Sex and the Failed Absolute. London: Bloomsbury.